You grew up in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and lived in Napa Valley in 1972. You are a self-made leader, a healer, weaving the energy of the stars, the cosmos, into the earthly plane for us all to reach our highest potential. Where did you first get involved in Human rights advocacy?

My involvement started in 1976, when the UN Human Rights convening in Nigeria came to my attention due to political involvements around Legality and accessibility of women’s healthcare around Midwifery and home births. At the time I considered being a delegate to the UN, however, due to the young age of my children I did not attend but began to intently follow the International Human Rights movement for women & children.

What motivated you? The lack of accessibility to reproductive healthcare choices for women. The dawning realization about how women’s choices in the job market, education and healthcare were so inferior and limited compared to men’s choices or options.

As a Native American woman what has been your experience?

Native American women and people are second or third- class citizens. The life expectancy is about 48 years of age. The incidence of police violence and sexual predation is the highest of any other minority groups in United States. Missing and murdered Indigenous women go unreported and the perpetrators go unprosecuted about 98% of the time. This is especially true on reservations in remote rural parts of the United States. This is just now beginning to change. The recent appointment of Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland is a long overdue turning point, as Secretary Haaland is making steps to address issues of Missing & Murdered women and the unresolved issues of Indian Boarding Schools in the United States. For the first time in U.S. History, Secretary Haaland has ordered the use of radar sonar equipment for body searching at the 300+ Indian Boarding School sites in United States. Similarly, Secretary Haaland has ordered historical records searches for identities, tribes and families where children were taken from by the United States Government. Pretty grim realities.

Discrimination and harassment are widely reported by Native Americans, across multiple domains of their lives and by Native American communities as a whole. You have been referred to as someone living “on the edge of mainstream”. As a human rights advocate for women and girls, as a healer and peacemaker, what has been your experience with the mainstream women’s movement and modern forms of discrimination and harassment against Native Americans?

Ummm, I think the biggest barrier is the lack of accurate historical information about what occurred in the Native American genocides in the United States. The gross lack of correct information makes it very difficult to have a coherent or relevant discussion. The still active repression of these historical documents is a major impediment to the dissemination of the historical truths of Native American history. The myths and lies created by US Government to pretend this was a “discovered Land!” Ignoring the sixty thousand years history of indigenous people who lived here in civilized, permanent villages and communities with rich complex lifestyles, sustainable land management and art etc. etc. Too long to really detail.

I know you are a 40-year resident and community organizer in Napa County California, a healer, dedicated to preserving Native American culture and building the cohesiveness of indigenous groups in the Napa area. You were and are the force behind “Suskol House” a 20 acres site in Northeastern part of Napa County built to preserve, disseminate and protect the Native American traditions, songs, dances, basketry and ceremonies of indigenous peoples of the Americas (Abyala). Can you share your journey? Oh, that is a very long story. The short version is the need to create a safe place for Indigenous peoples of the Americas to have ceremony and preserve Native American culture in relevant contemporary land base. Based on collective dreams, visions and need.

In early 1970s you became an organic farmer long before it was popular. It seems farming and gardening comes naturally to you and you are connected to nature in so many ways. You are also called “water expert” and helped authoring the Watershed Development plan for Napa County in its seminal years, 1992-1995, and served on the State Low Income Oversight Board, a committee of the California Public Utilities Commission. Drawing on your experience, how do you think we can we hold the land and Earth as sacred once again? Another long story very complex. But to recover and implement the indigenous land practices inclusive of spiritual components is essential. One Earth. One Air. One Water. One Fire. The base principle that “All life is connected.” Many projects after decades of organizing and public education at local, regional, State and international levels by indigenous peoples of the world since the euro-invasions and genocides that occurred here in US. Still occurring right now around the world are essential is rectifying this crisis. The crisis of Climate changes has brought a species extinction that might be the global WaKE up Point?

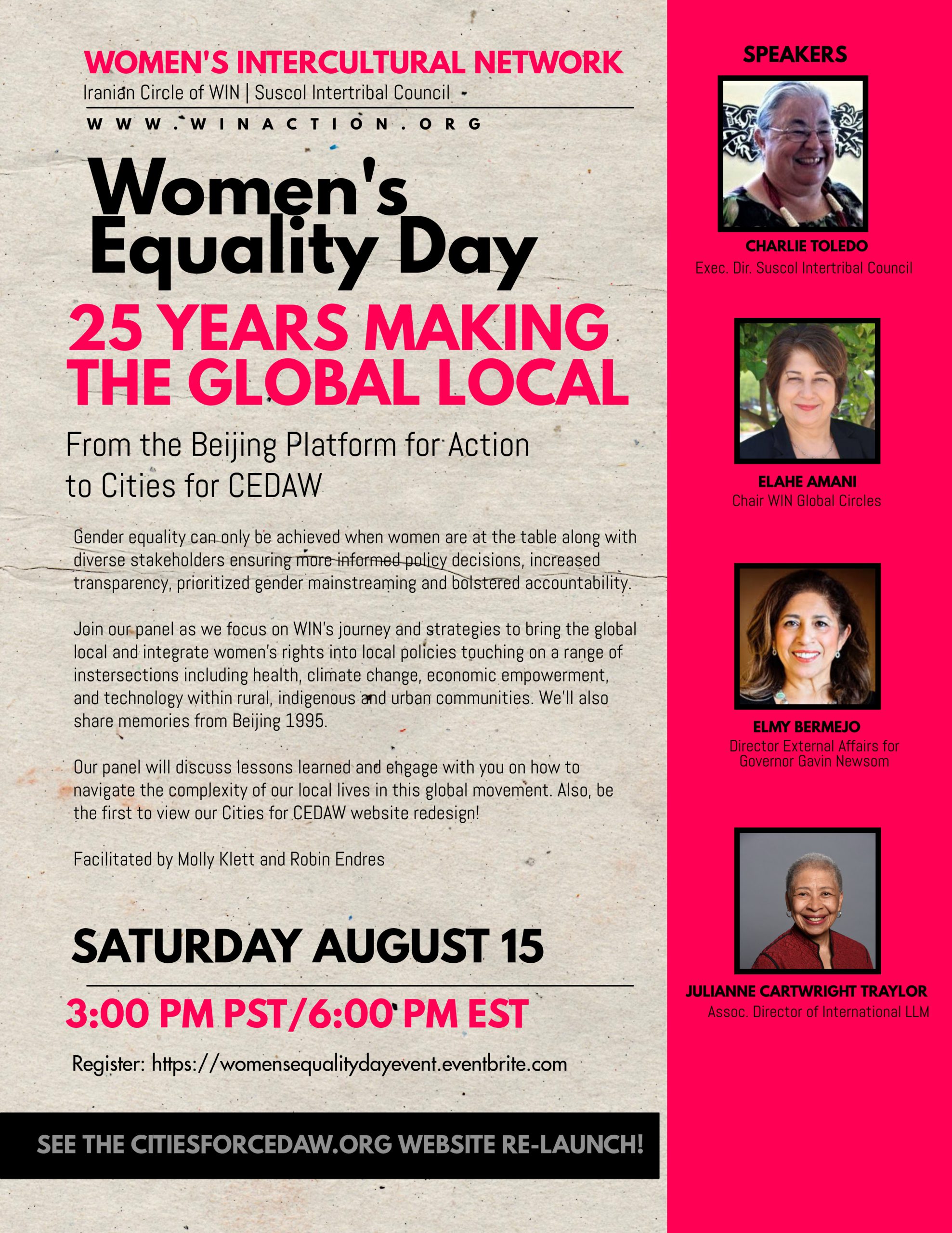

Ms. Charlie Toledo, you believe in creating positive changes for all through grassroots movements, one step at a time. How did you connect with Women’s Intercultural Network? What was your motivation? Marilyn Fowler’s charismatic leadership. Statewide convenings that occurred after the fifth Women’s conference in Beijing. Marilyn Fowler, CEO of WIN, really was the Spark point for so much of what was accomplished in Beijing 1995!

She connected with Apple computer to set -up a communication center on site in China! It was free and accessible to all participants. This was a primary tool for self-documentation for that herstorical conference. WIN orchestrated all of that! this was very visionary, as online emails were very new and emerging technology at the time. Again, under the incredible dynamic leadership of Marilyn Fowler, WIN brought women together to process the experience and create a plan of action after the international conference in Beijing and Huaren, China 1995. After the conference, Marilyn Fowler took visionary steps to develop a Plan of Action to implement the Human Rights platform developed in Beijing by convening with California state government Officials, Universities and organizations that resulted in collaborations with stake holders that resulted in the development of the Plan of Action.

This later evolved into a strategy for implementation of the Plan of Action for Women’s and Children’s rights at city levels. The goal to bring Human Rights for women and children to the communities where women live, work and study, not just at hypothetical international treaty levels. Finally, today cities exist where WIN women leaders “Bring the Global Local!” a focus strategy endorsed in 2018 by the United Nations. This is now being utilized as a working model globally.

Twenty years ago, you went to Afghanistan as part of the grass-roots delegation of Women’s Intercultural Network. With the recent political regressive changes in Afghanistan and Taliban talking control of the country again, can you share any reflection you may have?

The world is at the end phase of patriarchy. The misogynist, industrialized, unsustainable institutions are flailing about. This systems in collapse at the end of sustainability. The world has changed and will not change back. It is in dynamic transitions and will continue to evolve to sustainable compassionate and equitable societies.

What can advocates of gender equality, democracy and human rights can learn for future? Stay focused on what is becoming. Stay compassionate in the face of violence. Re-learn how to share resources, time. Slow down consume less share more. Focus on youth the future seven generations.